Many aspects of the academic book publishing process are mysterious to authors, even ones who have already published their books. It’s easy to get pulled through the process without knowing exactly what’s happening within the publisher or why you’re being asked to do this or sign that.

This post is about a topic that I see so much mystique and misinformation about (even from otherwise reputable sources): advance contracts. I hope to settle some questions and equip you with the general information you need to make the best decisions for your publishing process.

I also hope you will use this material to formulate your own specific questions for publishers when the time comes. If you’re offered any contract, you should feel very free to ask your publisher what it means and what it requires each party (you and them) to do.

What an advance contract is

An advance contract is a written agreement between an author and a publisher. It is issued by the publisher before the full manuscript has been submitted by the author and given final approval by peer reviewers and the press’s editorial board if it has one. This is why it’s called “advance” — the agreement is made in advance of receipt and approval of the full manuscript.

Most scholarly publishers will require some level of peer review before offering a contract. In the case of an advance contract, that might be review of a book proposal and sample chapter(s) only. In some rare cases a publisher might want to put your book under contract without a peer review process, but I would advise caution if that opportunity presents itself to you (more on that in a bit).

The “advance” in advance contract has nothing to do with an “advance on royalties,” by the way. If you hear an author saying they received an advance on their book, they’re likely not talking about the timing of the contract but rather about a sum of money the publisher has paid them upon signing the contract or at some later time. Advances on royalties are not super common in scholarly publishing, though some authors (even first-timers) do get them or negotiate for them as part of their publishing agreements. That’s a discussion for another day!

The difference between an advance contract and a “full” contract

The only difference is the timing, as explained above. In fact, the actual document you’re presented with by the publisher — the publishing agreement — will likely be identical (or very close to identical) whether you get it before you submit the full manuscript or after.

It’s worth understanding that the distinction between “advance contract” and “full contract” doesn’t make much sense in most of the publishing industry. If you were writing a trade nonfiction book, for instance, you would very likely seek a contract on the basis of a proposal before you completed the manuscript. In the majority of the industry, all contracts are advance contracts (but they’re just called contracts).

It’s only in academic publishing and perhaps in some other smaller, risk-averse sectors of the publishing industry where a press might not want to commit to a nonfiction book before seeing the full manuscript.

There is a boilerplate clause in most publishing agreements that is particularly relevant for authors who have not yet completed their full manuscripts. This is the clause that stipulates that the full manuscript is subject to review and must be approved before it will be published. Here’s what the relevant bit looks like in my contract with Princeton University Press for The Book Proposal Book:

“The Press’s publication is contingent upon the decision of our Editorial Board, at its sole discretion, that the final Work is, in form and content, worthy of publication by the Press.”

Again, this kind of clause is standard in the greater publishing industry, but this is the clause that scares academics about advance contracts, I think.

Yes, it allows the press to get out of publishing the book if they deem the manuscript unpublishable after putting the full manuscript through peer review and the editorial board approval process.

But this is not a clause that editors or presses want to invoke. If they are issuing a contract at all, that means they believe in the project and hope that it will come to satisfactory fruition for everyone involved.

Presses usually end up publishing the books they put under advance contract

There aren’t statistical figures on this (to my knowledge), but in a poll I ran on Twitter, less than 1% of scholars with advance contracts reported having the contract cancelled by the press. Another 1% of authors said they chose to break their own contract. The rest of the respondents (n= 131) ended up publishing their book with the press that gave them the advance contract. Those feel like great odds to me.

As I said above, a press that has invested time and effort into getting your book under contract wants that book to happen as planned. The main reason I can think of that they wouldn’t want to follow through would be if the author delivers the manuscript so late that the press’s publishing agenda or market has shifted significantly in the interim and the press feels it can no longer successfully launch the book.

The press may also lose interest in the book if the editor who acquired it leaves the press and the press no longer has anyone in house with the vision and investment to support the book as strongly as they would like.

(If you find yourself in the situation of having your editor leave your press, don’t worry immediately. Arrange a conversation with someone else at the press, such as the editorial director, so you can gauge their level of commitment and decide whether you want to stick with that publisher. They’ll likely release you from the contract without much fuss if that’s what you feel would be best for your book.)

I think it would be a rare occurrence if the project made it through initial peer review with strong enough support to land the advance contract and then didn’t pass muster at the later stage such that the press would automatically cancel the contract. I’m not saying it couldn’t happen, but I would hope and expect that the press would do what it could to help you bring your book up to publishable standards before they give up on it. That might mean multiple rounds of revision and review, but not immediate cancellation (unless you wanted to take the project elsewhere). Remember, they’ve already invested substantial time, labor, and interest in your project and will likely want to make good on their investment if they can.

What happens between signing the advance contract and final approval for publication

Your advance contract will stipulate a date by which you’ll be expected to submit your completed manuscript for further review. This will likely be the date you specified in your proposal as being your expected completion date, so it behooves you to be realistic. While you should try to adhere to this due date, there is usually some flexibility as long as you stay in communication with your editor. (For more on deadlines in book publishing, see this post.)

When you submit your full manuscript, the press will likely send it out to peer reviewers. They may be the same reviewers who commented on your proposal if they’re available. If your book is being published with a series, the series editor or series editorial board members may serve as reviewers.

If the peer reviews of the full manuscript come back with strong objections or substantial recommendations for revision, the press may ask you to revise and resubmit your full manuscript for further review. Your editor may send the revised manuscript back out to one or more of your peer reviewers, or they may ask you to write up a summary of the revisions you made and take that to their editorial board along with the peer reviews.

Of course no author wants to receive negative peer reviews or have to do a great deal of revision after completing their full manuscript, but this is sometimes just part of the process of making your book the best it can be. Again, I think it’s unlikely the press would drop the project altogether without giving you the chance to make revisions.

If you’re really concerned about the possibility of negative peer reviews, you can ask your press to add a sentence to your contract stating that they agree to communicate to you in writing the ways in which your manuscript is unsatisfactory and that they agree to give you a reasonable amount of time to make corrections or changes based on their feedback.

This is the way things typically work at scholarly publishers anyway—because this is how the peer review process is supposed to work—but you can ask for it to be put in writing formally, before you sign the advance contract, if you’re particularly nervous.

Once your editor feels the reviews are strong enough and that you have made all the necessary revisions, they will present your project to the press’s editorial board or publication committee. That group will make the final decision on acceptance of the manuscript for publication.

Again, I want to reiterate that it is highly probable that an advance contract will lead to publication as long as you hold up your end of the agreement by (1) turning in your manuscript reasonably close to on time (or communicating clearly about needing extensions) and (2) putting in a good-faith effort to engage with the peer reviewers’ recommendations. This doesn’t mean you have to do everything peer reviewers say, but a thoughtful response to peer reviews can go a long way with publishers’ editorial boards (see this post for more on how to respond to peer reviews).

Once your full manuscript is accepted for publication, you may be given a chance to make any final revisions you want to make before the production process begins. You will not be given a new “full contract” to sign at this point. You will not be able to renegotiate the terms of your existing contract. The advance contract is the contract.

Reasons why authors seek advance contracts

Some authors appreciate the vote of confidence in their project that an advance contract represents.

You may also benefit from receiving feedback from peer reviewers and your editor before you complete the entire manuscript. Working on your book in isolation before knowing that a press is interested could result in a lot of wasted time. What if you write the whole thing and then figure out there’s no audience or market for the book you wrote once you start trying to pitch it to presses?

Seeking an advance contract (or at least actively talking to your most desirable presses about your project) at an earlier stage could save you from going down a path with your manuscript that won’t help you achieve your publishing goals.

Another reason some authors like to sign a contract early on: an advance contract will include a due date for submission of the completed manuscript, and some people need that kind of put-it-in-writing motivation to finish or else they’ll put off submitting forever.

Downsides of an advance contract

While some writers thrive with deadlines and early feedback, others very much don’t. If you don’t want the pressure of a contractual due date, you can wait until you’ve got the manuscript finished or mostly finished to formally submit to publishers.

I’d still advise speaking to publishers earlier on, to at least get a sense that you’re heading in a viable direction. You can tell them you want to finish the manuscript before committing, though.

If you think it’s going to take you more than a year or two to complete your manuscript, you may want to hold off on committing to a publisher for your own sake. Your project and your career goals could evolve quite a bit in that time and a different publisher than you’d initially thought might turn out to be a better fit for the book you end up writing.

I would advise against signing a contract that’s offered before any part of your project is peer reviewed. The peer review process will give you a lot of insight into not only your project, but also how communicative and supportive your editor and publisher are.

You want publishing partners who clearly understand your book and its audience and who will be good to work with for the next several years. It might be very tempting to accept an offer that comes with seemingly little effort on your part, but I think you’ll ultimately feel better about the process if you and the press take a little time to vet each other first.

Some publishers don’t typically offer advance contracts for first books. If your dream press is one of those, I’d advise you to hold off on submitting proposals to other publishers. By waiting until you have the full manuscript complete, you’ll increase your chances of success with your top choice rather than being tempted by an offer from a press you’re less excited about.

Don’t assume that your top choice publishers don’t offer advance contracts, though. They are more common now than they were in the past. I’ve had clients sign advance contracts for first books with Princeton University Press, University of California Press, MIT Press, Yale University Press, and several others.

If you think you want an advance contract, go ahead and start talking to your target publishers to find out what the possibilities are. This could be a hypothetical question you ask in an early conversation with an editor. Or, when you’re ready to formally submit your proposal to a publisher, you can ask directly whether they think an advance contract would be possible for your project.

If they say no, don’t take it personally. Just plan to get back in touch when you have the full manuscript complete, if the press and editor still seem like a good fit at that point. (For more on how to talk to editors at various stages of the process, see this post.)

Once you sign a contract, it’s bad form to break it because a press you like better comes along with interest in your project. You may be able to do it — because most publishers will not want to work with someone who no longer wants to work with them — but you may burn a bridge in the process.

If you’re not fully certain you want to publish with a particular press, don’t sign a contract with them until you are certain. It may feel awkward to tell someone who’s interested that you’re not ready to commit, but it will be way more awkward to try to get out of the contract later.

How academic institutions view advance contracts

You may have heard that advance contracts don’t count for much for the purposes of hiring, promotion, or annual reviews. I think this varies a lot by department and institution. I have one client who was told that if she landed an advance contract for her book, her non-tenure-track position could be converted to a tenure-track position, and this ended up actually happening! Other institutions don’t consider an advance contract to be worth much at all.

If the question is whether you’ll actually finish the book you have under contract, that’s a fair reason not to count an advance contract as equal to a manuscript fully accepted for publication, and I can understand why an institution would not count them the same.

If the question is whether an advance contract means the publisher is actually committed to publishing your book, I think that question reflects a lack of understanding of what an advance contract is. For instance, many of the authors I work with have been told that “an advance contract binds them to the press but doesn’t bind the press to them.” This is just not true. An advance contract is a real contract and it binds both parties who sign it. Yes, it can be broken by either party, but this is rare.

Unfortunately, beliefs about the value of an advance contract can have a material impact on your career, so it’s good to be aware that some people don’t think advance contracts represent a real agreement to publish.

If you are receiving the message that your advance contract would not count in the ways you need it to at your institution, you may want to ask your publisher to write a letter of support that can be shown to the relevant parties to assure them that your press is indeed committed to publishing your book.

It’s also important to be aware that not all publishers are perceived equally. An advance contract from a press that is not seen as a leader in your field may not do you any favors on the job market.

You may ultimately be better off waiting until you can have conversations with people in your field and institution to find out which presses are likely to be looked on most favorably. Again, bear in mind that people’s perceptions don’t necessarily correspond to realities of publisher quality—and I don’t want to encourage anyone to play into a false hierarchy of publishers—but perceptions do matter in the academy so it’s good to at least be conscious of them if you have academic career goals.

If you aren’t sure you will even end up at an academic institution, your preferences as far as target presses could change. You may decide to write a different book altogether or not to write a book at all. This could be a point in favor of waiting to commit to a publisher until you are somewhat settled in your career direction.

Are you still trying to decide if seeking an advance contract is right for you?

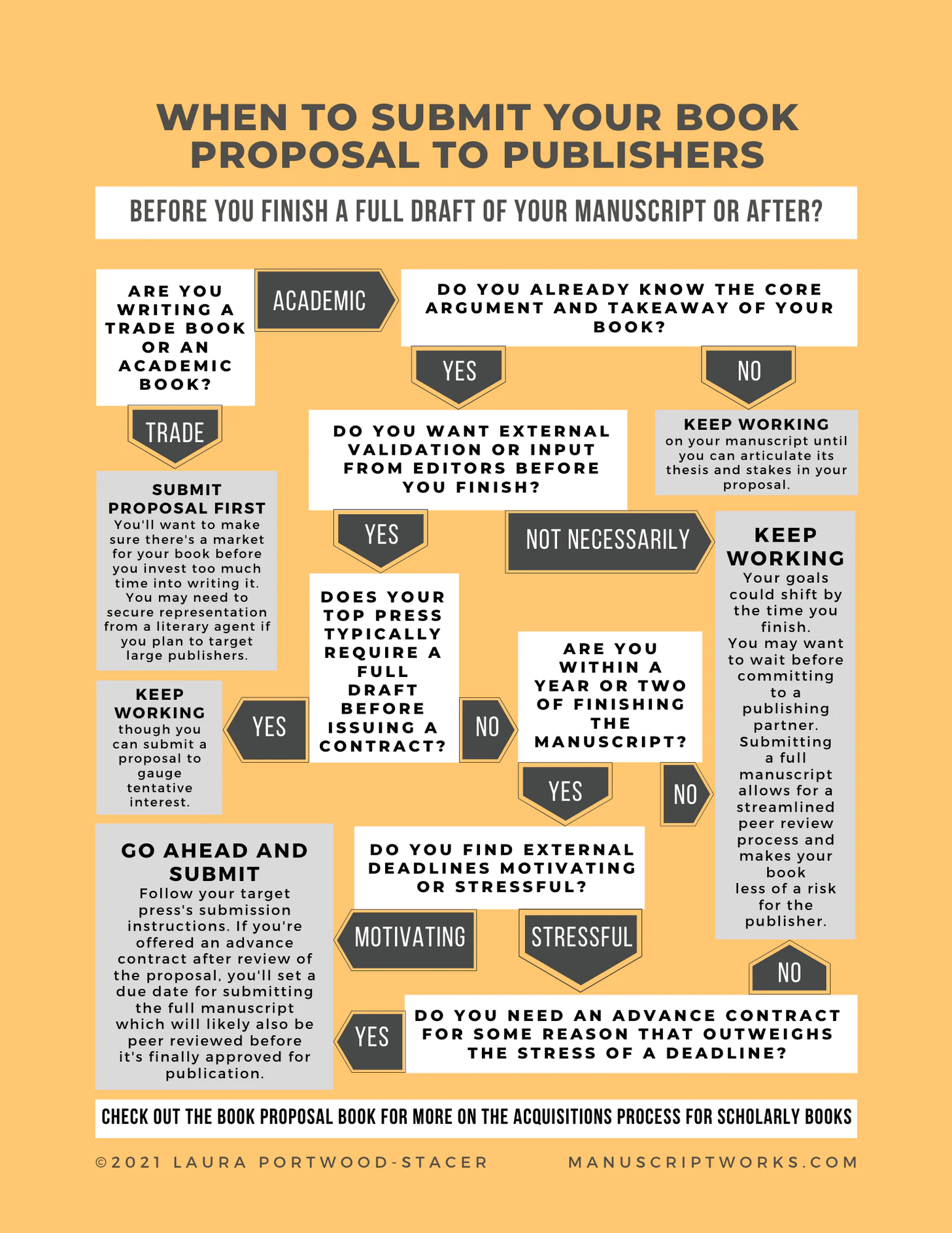

You can read this essay I wrote for Inside Higher Ed on the best timing for submitting your book proposal. I’ve also translated the content of that essay into a more visual format — you can download this decision tree PDF below.

Download PDF

If you’re not able to see the PDF, please check out the article.

What other questions do you have about advance contracts? What other myths have you heard? Have you had an experience with a publisher that you think I should know about? You can contact me here.

If you find this kind of demystification of the scholarly publishing process helpful—and you’d like personalized support as you prepare to submit a book proposal to publishers—you may want to check out my online programs.